A few weeks ago, I heard on the news that the great Chuck Berry had passed away. A conversation I had with my grandma about it went something like this:

“Grandma, did you hear that Chuck Berry passed away?”

“Yeah I know. Oh I loved him! That thing he would do with his leg, how he played on his guitar… “

“What was your favorite song by him?”

“Oh man… how can I pick? Maybe ‘Maybellene’, or ‘Johnny B. Goode.’ I liked all-a his songs!”

I felt bad now, because speaking honestly, I knew of his name and that he was great, but I did not know much about Chuck Berry. But the way she spoke of him with such admiration and respect made me want to research more about his life and musical career.

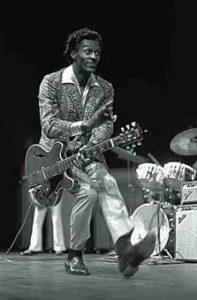

Chuck Berry was born and raised in St. Louis, Missouri. He composed, wrote, and played his own music. He also played the guitar in interesting ways, like doing a “duck walk,” or by sticking one leg out:

He died in Wentzville, Missouri at 90 years old. There were many songs of his to choose from, but I decided to look at the songs that my grandma mentioned: “Johnny B. Goode” and “Maybellene.”

Johnny B. Goode

The first song, “Johnny B. Goode,” was written by Berry in 1955 and recorded by him in 1958. This song sounds great is one of the most iconic songs in American history, and it is commonly used in shows and movies (including one of my favorite movies, Back to the Future). “Johnny B. Goode” is the story of a boy who plays the guitar and wishes one day to become famous. In this song and many others, Berry was able to mix black and white elements in a way that hadn’t been done prior; through his lyrics, he portrayed the everyday life of white American suburban folk. The music itself was inherently black American: the roots of the song were grounded in the 12-bar blues progression. This progression traces back to, and is in essence, wrought from slavery in America.

“Johnny B. Goode” made this 12-bar blues progression, and a black man’s story, marketable to mainstream audiences. But this marketability did not cone without challenges. He was famous during segregation, a time when it was legal to discriminate against blacks. In order to get his song on the radio, he had to take out any mention of blackness: “The original words [were], of course, ‘That little colored boy could play.’ I changed it to ‘country boy’ — or else it wouldn’t get on the radio.” (Rolling Stone) Even still, he was able to make blackness appeal to mainstream audiences. Many artists have said they were inspired by him, with a few being the Beatles, and The Rolling Stones, and many artists use some of his riffs.

(There is a list of covers that other artists have done on Chuck Berry’s website, here.)

Another song of his, “Maybellene”, adapted from Western song “Ida Red”, is seen as a pivotal song in Rock. This song was able to mix sounds of R&B, country, and blues, something that was unheard of during the 1950s. Berry recorded this song in 1955. The song also inspired a relatively unknown artist at that time, Elvis Presley, to record his own cover of the song. Elvis Presley, contentiously dubbed “The King of Rock & Roll,” has covered many of Berry’s songs.

“Maybellene” was also groundbreaking for its guitar solo: Berry played his guitar in a way that was unable to be duplicated (specifically, during the parts [1:22-1:28] in the video link). Another artist who grew inspired from Berry’s style of playing was the late Jimi Hendrix.

According to LifeZette, Hendrix also spoke of how he was influenced by Berry in his biography: “[T]he late Hendrix said Berry was his favorite artist, according to the Hendrix biography ‘Crosstown Traffic.'”

Chuck Berry was a risk-taker who experimented with sounds in music, and he in turn inspired many other groundbreaking experimental artists. His sound was innovative: it made rock and roll. And even with all of the innovations Berry made in the genre of rock, he wanted his music to feel, in his own words: “Simple — at least I hope it to be.”

Shayna, this is a great example of using hyperlinks and various media to support your piece of writing!

The issue you mention of Chuck Berry needing to change the words of his song to hide his blackness is very provocative and worth discussing together in class. The idea that a man, who is clearly black, would create music that was popular enough that a white man would take it on (Elvis) and “sound black” and yet words would need to hide the race of the creator, something that is plainly obvious, seems perhaps ludicrous to us today. Yet is evidence of the suppression of black voices that persisted in the 20th century.

What can we do today to undo this suppression? Your post is a great action, telling stories and raising awareness.