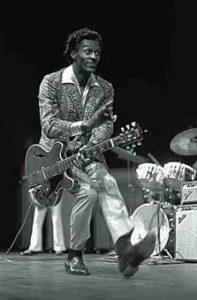

Photo Courtesy Amoeba.com

The Dream House is such an individual experience that describing it in words may not do it justice. But, I will try.

The Dream House is a room with four speakers that plays sounds at different frequencies and was made in the 1993 by La Monte Young and his wife, Marian Zazeela as a culmination of years of work. A list of Young’s works can be seen here. The House itself is intriguing at first sight: a carpeted purple-magenta room, not very big in size, with incense that fills the room. The purple filters on the windows make it impossible to tell how much time has passed, and what felt like 10 minutes in the room actually ended up being an hour and 20 minutes. Though the room is small in size, its range of sound is huge. Literally every area of the room had a different sound. Walking in, turning my head, sitting up, and lying down all sounded differently.

The feelings of each pitch ranged from soft on the ear to buzzing to slightly thumping on it like a hammer. The pitch of each sound did not change, but each sound itself was different. The dynamics of the sounds ranged from whisper-soft microphone-screeching feedback, to low ‘wah-wah’ sounds, to the hum of a running AC. The range of sound was so vast that I am almost certain there were sounds being played that my human ear could not pick up.

The speeds of some sounds stayed constant, and the speeds of others moved as my head moved. I did a mini-experiment: I attempted to follow three waves of sound as I turned my head. Looking straight forward, sound A was a low oscillating sound, sound B was a mike-feedback, and sound C was a high tone. I turned my head slowly to the left, and turning left: sound A stayed, and sound B intensified like a person who slowly turns a flashlight towards you until the light beam hits you straight on. Sound C sped up like the sound of a bomb about to detonate until — the sound completely disappeared.

A picture of the wave spectrum in my head had appeared, and then I thought: what would the room look like if all of the vibrations in the room were able to be seen visually? In my head, I expected the high pitches to not be heard lower to the ground. To test that theory, I lay down. My theory was proven wrong as the same high pitch from before remained, and a new drone-sound previously unheard appeared.

Then I sat up again and looked around at about 17 other people in the room. At that moment I had a crazy realization. At a typical concert or music performance, people usually listen to an artist and heat the same thing. But in the Dream House, although we were all in the same room, with the same four speakers, none of us were hearing the same thing. The Dream House was unlike anything I’ve ever experienced. It was weird, and it was beautiful.